There’s so much I want to talk about with this show—not just the ending, but so many moments along the way. I want to talk about all the episodes that made me cry; about the beauty of “A Life in the Day”; about Margo’s desert journey with lizard-king Eliot; about how much I want to believe in a swearing Santa Claus who gives exactly the things you don’t know you need. I want to talk about the cruel whimsy of gods and the incredible skill with which the show’s writers balanced people doing shitty, selfish things with deep understanding of exactly why they were doing them.

I want to talk about Alice, and how so much of her anger comes from how much she doesn’t change enough, how she’s brittle and wise and always scared of losing, and how that doesn’t protect her when the loss comes. I want to talk about destroying in order to create, and that smile on Margo’s face at the end. And I want to talk about how these characters aren’t heroes.

They aren’t anti-heroes, either. The Magicians isn’t a show about redefining what it means to be a hero, but it is, in part, about asking whether that’s even a useful way to measure anything. It’s what Quentin Coldwater has to get over: the dream of being a chosen one. It turns out that it’s a lot more effective to simply do what needs to be done, even when it’s the opposite of heroic—when it’s robbing a bank or tripping magic balls or literally bottling up your emotions or just accepting the good and bad of your internal circumstances.

But that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

By the end of the first season, Quentin knows he’s not the protagonist in a story like the ones he grew up loving: “Every book, every movie, it’s about one special guy. Chosen. In real life, for every one guy there are a billion people who aren’t. Almost none of us are the one.”

When it comes time to face the Beast, the right choice for Q is not being the person who fights. His knowledge of stories has already helped them—saved them—time and time again, but in that fight, his role is to not be the hero. Alice does the heroic thing, and Alice dies. (Mostly.) As the seasons go on, they save each other, over and over, by not being the hero. They do it by stealing and lying and jumping timelines and swapping bodies and breaking into song. They do it with treachery and destruction and releasing the kraken and still, sometimes they die.

At the end of season four, Quentin makes a choice, knowing full well what will happen, and he dies. There are no take-backs, no astral-plane jobs, no return trips from the Underworld train station for him. There are thousands of words to be written about Q’s choice, about what it means and what it says about the idea of sacrifice, about how the story works and doesn’t. I sobbed for twenty solid minutes because it worked for me, though I understand it didn’t for everyone. At Vox, Emily Todd VanDerWerff wrote a perfect piece on that finale.

I want to talk about what came after: The Magicians went headlong into grief. The fifth and final season skipped over denial and anger and went right to the other three stages: bargaining, depression, acceptance. Is there a reason to get out of bed? Can a person be brought back? Can doing something crazy help? Can people grieve together, despite what Alice’s mother says about grief being a journey you take by yourself?

They can—especially when they’ve had so much practice. Because this show has been about grief all along. It just didn’t snap into full focus until they were all grieving for the same reason.

***

Buy the Book

Trouble the Saints

The Magicians ended its very first episode with a death, but the fresh-faced Brakebills students barely knew their murdered professor. What they lose is their sense of security, and their illusion that their world is a safe place. But partway through that first season, grief and loss become a major thread for one character, and no one seems to pay any attention.

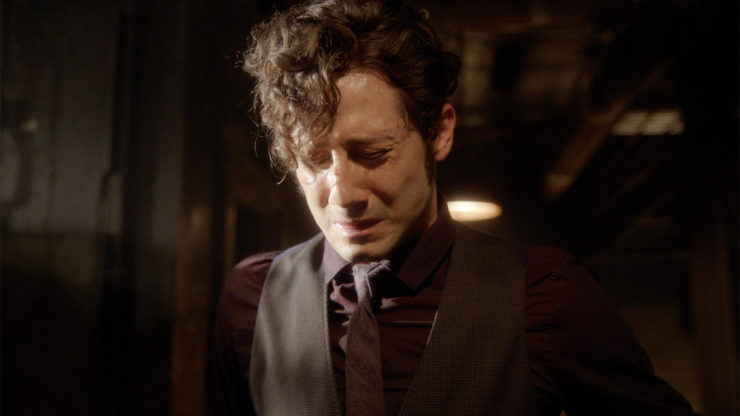

As is so often the case, I’m talking about Eliot.

In “The Strangled Heart,” a lot goes wrong. Penny is stabbed with a magical knife (meant for Quentin) that gives him a magical ailment, which is where most of the gang focuses. But Eliot has a different problem: the person who stabbed Penny is El’s Beast-possessed boyfriend. And at the episode’s end, it’s just Beast-Mike, injured Dean Fogg, and Eliot, in a dark hallway.

Even in its first season, The Magicians is rich with things to love, with screwed-up characters to root for, with clock trees and mysterious Chatwins and hedge witches. Over the years, so many scenes played on repeat in my head (including “One Day More,” a song I do not know outside of this context). The coronation. Alice reluctantly connecting with Santa Claus. Margo with her axes. “Peaches and plums, motherfucker.”

But I trace the way I watch this show back to this moment.

I waited the rest of that season for anyone to mourn with Eliot. To understand why he was bitter and inattentive, even drunker than usual, self-medicating without the faintest bit of joy.

No one did, though Margo tried, in her way. And of course they didn’t. They were all dealing with their own shit: trying to figure out how to kill the Beast, how to survive, how to deal with the reality of Fillory, how to get their hands on or control magic. So Eliot wallowed and suffered alone, and then discovered he needed to become High King of Fillory—at great personal cost.

I was furious. No one saw his crushing pain and here he was, trapping himself in magical marriage to a woman he didn’t even know! While still messed up by what he’d had to do! Why did no one else realize how much he was going through?

But there was so much I didn’t realize yet, either: how far this show was going to veer from Lev Grossman’s books. How many ways they’d find to circumvent the one-sex-partner-forever law of Fillorian marriage while letting El grow in the process. And how many ways these characters were going to learn to grieve losses—of life, of freedoms, and of so many other things—over the next few years. There’s so much loss. Betrayals, heartbreaks, deaths, terrible mistakes. Every character has their version of what Eliot goes through; everyone loses someone, and everyone does something terrible.

Alice dies, becomes a niffin, becomes human again, full of rage about the knowledge she’s lost. Mourning Alice, Quentin abandons Fillory. Julia suffers so much and then loses her shade, which leaves her unable to grieve—not for what’s happened to her, and not for what she’s done. At the end of season two they save Fillory, but lose magic. At the end of season three Alice betrays them and they lose Eliot to monster-possession. At the end of season four, they lose Quentin.

***

Loss is personal—no one aches the same way—but they lose Quentin together, and that’s what makes the grief of season five so monumental.

The Magicians is a show about people losing things and growing up, and you can’t have the growth part without the pain. And magic, in this world, comes from pain.

It’s Eliot who tells Quentin that little magical fact, way back at the start, and Eliot who demonstrates it when he kills Beast-Mike. We’re told, so often, that pain is something to avoid, but The Magicians takes a different approach: pain is unavoidable if you love. You can say Julia gets magic back because of the pain she feels at losing Quentin. You could also say she gets magic back because she loves him.

Pain isn’t what these magicians’ friendships are built on, but getting through the worst things strengthens them, pushes them closer to vulnerability and honesty and connection. When they met, they didn’t know how to do that. That’s what left Eliot so alone in season one, and what sent Quentin back to a dreary “normal” life in season two. They had so much to learn about working together, and about being together. By the time the story ends, no one is going through hell alone. No one is overdosing alone, or questing alone, or mourning alone. Especially not Eliot, who sends himself on Alice’s quest to the Mountain of Ghosts, going along as if she might need him—and she does, though not the way either of them expected. He needs her, too.

In season one, when Eliot was drowning in grief, the show took Margo away for a few episodes, leaving him without his best friend to lean on—and when she came back, they argued and bickered and didn’t know how to balance each other. But look at these two in “Oops!…I Did It Again”—the one with the whales, the kraken, and the time loops. Look at Eliot’s honesty when Margo’s reassurance isn’t enough to convince him that the monster isn’t still inside him. And look at their conversation when Eliot saves the world. They face up to everything. They accept everything. Including the fact that Eliot isn’t just a witty drunk; he’s capable and smart and he needs to be those things for himself, not just to avert the apocalypse. For the first time in a long time, Eliot cracks a real smile.

***

Magic, in this world, is hand movements, math, language, a whole toolset of things, and it’s affected by circumstances: temperature, direction, the moon, all kinds of details.

But in this last season, as they study the metamath needed to move the moon, our magicians become aware of another kind of circumstances: internal ones. Magic comes from pain, but it’s not just your pain that affects your magic; it’s you. All of you. And that’s the only thing you can really control.

Of course it’s Alice, the knowledge seeker, who understands this first, best, and maybe most painfully. When she tries to create a golem Quentin who can read the page she found in a drawer, what she gets is a tween Quentin who talks to her—and Julia—about stories, instead. One who freely admits that he hates endings, and can see what Alice wouldn’t admit to herself: “I can’t help you because you don’t want me to. Because then your friend’s story is over.”

Season five is most overt about Alice accepting her story as her own (thanks, Santa Claus!), but it’s true for all of them. Margo accepts responsibility for Fillory to the point that she’s willing to sacrifice herself, and she accepts her feelings for Josh. Penny accepts fatherhood and family, and regains his powers in the process. Fen stops letting everyone’s idea of her define her; she steps up, defies her friends’ expectations, and accepts the entirety of her self and her world, flaws and all. Eliot faces and accepts everything he’s gone through, and lets himself be vulnerable to a new connection.

Internal circumstances are specific to you; grief is specific to you. Two people who mourn the same person don’t mourn the same way; they don’t have the same story. They can’t. The Magicians allows for paralyzing grief, the kind where you don’t want to get out of bed. It shows the kind that’s desperate to create balance, to make life mean more in the wake of loss. It shows the kind that wants to drown and the kind that wants to use magical thinking to change the past or fix the present. It shows that each person isn’t limited to one way of grieving.

“Accepting internal circumstances” is another way of saying something that was said to me a lot when I was a very anxious teenager: “You can’t control how people react to you. You can only control what you do.” It’s another way of drawing a circle and sorting out what’s in your control, inside the circle, and what’s not. It’s another way of saying: it’s ok to be hurting and feel broken and lost. Just take those things into account while you’re doing what needs doing.

And it’s a way of saying what these magicians all had to learn: all of these things, the good parts and the bad parts and the ugly parts, matter. Working around them isn’t effective. The only way out is through. You can’t just ignore the bad parts and carry on—not in your friends, and not in yourself. You have to keep checking in, internally and externally, and keep accounting for what’s going on with you. There is no mastery without doing the work.

Obviously the showrunners and writers didn’t know these final episodes would run during a global pandemic, when illusions about what we can control are thinner and flimsier than usual. But they do clearly know that accepting one’s internal circumstances is incredibly difficult work. It’s not a 101-level lecture for first-year Brakebills students. It’s not a thing you learn in class. It’s a skill hard-won after facing the truth of yourself. After being through some shit. And after letting your friends see you as you are, too.

You can only account for yourself. You’re not going to be chosen. You’re not going to be a hero. You’re going to be better at doing what needs to be done if you accept the whole mess of who you are.

That’s some real goddamn magic.

Molly Templeton has been a bookseller, an alt-weekly editor, and assistant managing editor of Tor.com, among other things. She now lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. You can also find her on Twitter.

Wonderful summary! I have been thinking about all these things, but you put it into words beautifully.

I can’t believe there isn’t a new episode tonight. :(

It’s difficult to define the level of briilance to this show. From the writing, the intricate woven plot lines, the amazing actors that fully embody the fascinating and downright Beautiful to look at characters with all their intricacies and complexity. The way you just feel deeply for every single one of the main characters. You rejoice when they do, cry when they do and FEEL something in every episode. The climax was brilliant and I’m sad to see it end.

Very well written article!

This is a beautiful summation as I, too, mourn the end of this series.

Due to what has to be the worst case of synchronicity, ever, my best friend died right before the pandemic really hit, on Valentine’s Day or early the 15th. I’m mourning him, mourning the show, mourning the losses we’ve seen and the worse losses that are coming. All the grief has been nearly unbearable…then i came across things article: a beautifully written reminder off things that i knew but are also hard to hold onto when your entire world is wrecked. These words were exactly what i needed, thank you.

@5 – I’m so, so sorry for your loss, and I’m honored that I could help in some small way. I hope we can all hang in there through all this wreckage. <3

Thank you for this. This show has meant so much to me and Q was a character I connected with a lot.. And I really liked the ending to season 4. It felt right to me, even thought I understand other people’s issues.

But all I saw online was negativity and it really sucked because I wanted to be able to mourn one of my favorite shows. Something that meant a lot to me.. So thanks for giving a space. I needed this.

The last 20 minutes of season 4 finale are painful to watch. Everyone’s reactions and memories are so heartfelt. But it’s after Q’s “Magic comes from pain.” cut back to Julia, sitting by herself next to the fire, sobbing. That’s one of the hardest hitting expressions of grief I’ve ever seen. I’m tearing up remembering it to type this. Man, that hurt.

Thank you for a wonderful and emotional summary. I have loved these characters from the beginning. so So sad to see the show ending, but I really loved the way everything was wrapped up. It felt very satisfying.

Yes! A fantastic read! Thank you.

Wonderful article. Thank you for a beautiful summation. There were so many things about that series that I love.

I can’t say I found anything like it. But I hope something comes along to fill the void that The Magicians ending left in my life.

Best!

Huh, nothing about Kadi…

I cried all along. That’s a very acurate and deep reading of The Magicians, and I really want to thank the writer for her wonderful writing. I’m going to miss them all…

Really? One Day More?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sv-BxH3SVS8

With the food and knife trees, it occurs to me that the new Fillory may be a nod to Oz. I always liked Oz more than Narnia.